Catch-Up Contributions

What Is a Roth 401(k)?

April 21, 2022Systematic Withdrawals in Retirement

April 21, 2022RETIREMENTREAD TIME: 4 MIN

A recent survey found that 23% of people were very confident about having enough money to live comfortably through their retirement years. At the same time, 33% were not confident.1

Congress in 2001 passed a law that can help older workers make up for lost time. But few may understand how this generous offer can add up over time.2

The “catch-up” provision allows workers who are over age 50 to make contributions to their qualified retirement plans in excess of the limits imposed on younger workers.

How It Works

Contributions to a traditional 401(k) plan are limited to $19,500 in 2019. Those who are over age 50 – or who reach age 50 before the end of the year – may be eligible to set aside up to $26,000 in 2019.3

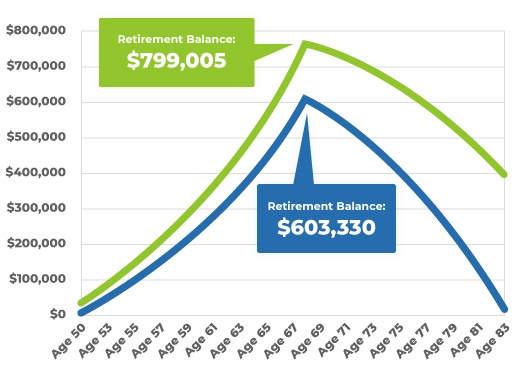

Setting aside an extra $6,500 each year into a tax-deferred retirement account has the potential to make a big difference in the eventual balance of the account. And by extension, in the eventual income the account may generate. (See accompanying chart.)

Catch-Up Contributions and the Bottom Line

This chart traces the hypothetical balances of two 401(k) plans. The blue line traces a 401(k) account into which the maximum regular annual contributions are made each year, but no catch-up contributions. The green line traces a 401(k) account into which the maximum regular and full catch-up contributions are made each year.

Upon reaching retirement at age 67, both accounts begin making payments of $4,000 a month.

The hypothetical account without catch-up contributions will be exhausted by the time its beneficiary reaches age 83.

This hypothetical example is used for comparison purposes and is not intended to represent the past or future performance of any investment. Fees and other expenses were not considered in the illustration. Actual returns will fluctuate.

Both accounts assume an annual rate of return of 5%. The rate of return on investments will vary over time, particularly for longer-term investments.Contributions to and withdrawals from both accounts have been increased by 2% each year to account for potential 2% inflation.

Under the SECURE Act, in most circumstances, you must begin taking required minimum distributions from your 401(k) or other defined contribution plan in the year you turn 72. Withdrawals from your 401(k) or other defined contribution plans are taxed as ordinary income, and if taken before age 59½, may be subject to a 10% federal income tax penalty.

1. EBRI, 2019 Retirement Confidence Survey

2. Economic Growth and Tax Relief Act of 2001

3. Forbes, 2020. Catch-up contributions also are allowed for 403(b) and 457 plans. Distributions from 401(k) plans and most other employer-sponsored retirement plans are taxed as ordinary income and, if taken before age 59½, may be subject to a 10% federal income tax penalty. Under the SECURE Act, in most circumstances, you must begin taking required minimum distributions from your 401(k) or other defined contribution plan in the year you turn 72.

The content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information. The information in this material is not intended as tax or legal advice. It may not be used for the purpose of avoiding any federal tax penalties. Please consult legal or tax professionals for specific information regarding your individual situation. This material was developed and produced by FMG Suite to provide information on a topic that may be of interest. FMG Suite is not affiliated with the named broker-dealer, state- or SEC-registered investment advisory firm. The opinions expressed and material provided are for general information, and should not be considered a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. Copyright 2022 FMG Suite.